|

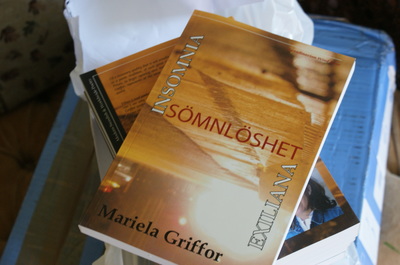

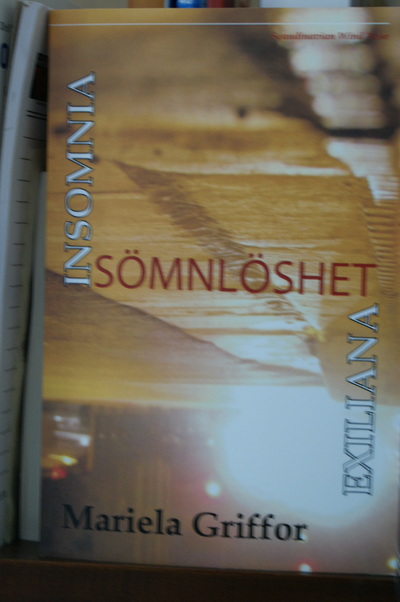

Sömnlöshet by Mariela Griffor/Ars Interpres Publications, Stockholm, Sweden/

2015/212 pages/ €23,00 EUR/ ISBN: 978-91-980386-6-8 Orders: Alexander Deriev/Tingvallavägen/195 31 Märsta/ Telefon: 08-59113267 When Alexander Deriev, who has a deep understanding and appreciation of poetry, called and told me he wanted to publish a trilingual book (Sömnlöshet) of my poems, I laughed at first. I wondered immediately just how many people would buy such a rare sort of book. I had once been listed years ago as “an author of rare books” together with some others regarded as cult writers – which I took great pleasure in – but then I thought: We enjoy the privileged amount of “just a few” that read our work! Though the thought was amusing, deep inside I was flattered, very flattered. I knew Deriev was a connoisseur of poetry and that gave me a great feeling and, at the same time, a little bit of pressure of responsibility. Immediately my mind tried to find ways of releasing the tension, the pressure. I told him immediately “Yes”, but that he should not be disappointed if the sales of the book were low or even minimal. He said he didn’t care. So I thought, here we are, two bibliophiles, talking about a trilingual book that perhaps nobody would read. The world is stranger than I thought. At least I like this kind of strange, at least this path does not involve killing or impoverishing people, right? Or maybe the world had always been this multilingual, multicultural, and it took a while for us to understand that fact, until the arrival of globalization! When most of the publishers and writers (and editors of course!) are preoccupied with the number of sales, we were immersed in the discussion of what language should be first or second or third in the book. We decided to go with Swedish first. Swedish is an extraordinarily beautiful language but it is largely unknown outside Sweden. However since the book is to be distributed primarily in Sweden we decided to go with Swedish first, then English and Spanish. Alexander’s wife, Regina Derieva, had been suffering from a lengthy illness and for several years he took devotedly care of his wife until she died in December of 2013. Now, when he was returning to previously planned projects, the world was not the same anymore; it had become global and I have seen several bilingual books emerging from different parts of the world and even some trilingual anthologies. We began to put together strategies for the book and finally, voila, here it is standing proud among other similar ideas for multilingual books. Thanks to Alexander Deriev and Lars Ahlström, the translator, this book is not only possible but is a reality today. Who would have thought that possible five years ago! I’m proud of belonging to Alexander Deriev’s list of writers, as are many others who have published with him like Per Wastberg, John Kinsella, Dipak Mazumdar, Les Murray and many more. He is not only a member of the literati but is also a publisher-hunting- for-poets-around-the-world! Buy the book here and let me know what you think! http://arsint.com/book_m_g.html My email address is [email protected] Mariela Griffor Dear Friends,

This summer has been a summer of surprises and big changes. Not only have I moved (or at least I will be living between two zip codes, Michigan and Washington D.C.) but also I got a new desk, which is quite modern, quite small, and greatly practical. The best desk I have had in years! I’m sure I will be able to keep up with the fierce discipline of my many new media writer friends. The distractions are many but I’m still good with deadlines and that is my best friend these days. Many of you have written to asking me an update on my Canto General translation from Tupelo Press. I received a very kind letter of explanation from my publisher posted for all those who supported the project. I would like to share the update and also my thanks for your interest and support! Below you can also find one of the photos of Neruda’s last residence. The photo credit of from Hector Goonzalez de Cunco. I will share more photos of multiple visits to Neruda’s house in Isla negra and other of his houses in a facebook page I started for this publication. Go and like the page if you can. The first volume of the book will be coming out mid Fall 2015 and I cannot express how excited I am! As you know Tupelo Press is a press with an incredibly hard working team and they are busy year round with literary projects that increase the interest for literature, poetry, translations and more. If you have the time, take a look at their pages and authors! I will try to keep a weekly update from now on about the detailed work and photos surrounded the production of this book starting with the collaboration with my editor – I will chronicle the story of this translation. I’m very glad to finally reach the point of getting the book ready. Here is the new update on the translation of the Canto by Neruda from my publisher! Best, Mariela ********************** Neruda update! To Our Dear Backers, Here at Tupelo Press Mission Control, we are hard at work putting the finishing touches on the Canto General translation drafts, though clearly we're not going to make our April release projection! Delays are usual in publishing, and especially in nonprofit publishing. In addition to polishing the translations, we're also in the process of determining whether this project will be even more exciting if published in two volumes (with a slipcover for both), or in specially-designed editions, one for each Canto. Either way, we'll have all our decisions made, the drafts finished, and on to the designer by summer's end, and first volume(s) out in mid-autumn. Meanwhile, so many thanks to all for your continued support. This will be by far the largest publication project we (or most any independent publisher) has ever produced--and one of the most important--and we hope to have spectacular results! We'll start sending out volumes to backers (whether the first of two, or the individual Cantos) as they come back from the printer. All our best regards, Jeffrey Levine, Tupelo Press As one of my new year’s resolution list, I will deliver all those mini-reviews I promised to friends and readers who often send their work to me in order to get some feedback. It is difficult to get a review for all those books pouring in, but here are some books that caught my attention.

I’m late in comparing with the date of the book publication, in delivering but not that much if you consider a review is valuable at any time. We are so incredibly pressed to get some feedback for our work as soon as the book comes out that often we forget that a review is important also, no matter when it comes out. I had one of my own books reviewed literally years after it was published. My thanks to the writers who always think that I would have something interesting to them to say, especially to Eric Torgersen and Jorge Etcheverry, who are always updating with fresh material. I will be posting more of these in my blog when time allows it. Apocalypses with Amazons Reviewed by Mariela Griffor Author: Jorge Etcheverry Publisher: Editorial Antares: http://www.glendon.yorku.ca/antares/english/editorial.html I like very much the tension of existential discharge contained in the pages. I like the feelings of anxiety and brusque, or better said the brutal, mental fracture that comes from some of the short stories in this collection. The shortest of these stories, and the one that bears the title of the book itself, Apocalypses with Amazons, is my favorite. It took me years to understand the work of Etcheverry and I’m not saying this for it being a lesser qualification but rather for its surrealistic complexity. It is representative of the works of the School of Santiago, created in the sixties whose slogan was “Here exists neither poetry nor prose: here exists only The Word.” A linguistic slogan that included later on the cultural class of exile. Apocalypse of the Amazons is different from other books of magic realism coming from Chilean expat Etcheverry, it is precise and chooses his characters carefully. He portrays the feminine characters as strong, attractive, smart, vulnerable and as intellectuals. His feminine characters never subdue. Many times these women are stronger, wiser. I’m not surprised that an author like Etcheverry had strong political views that creates an environment where reality is ‘fixed’ into an ulterior development where human values prevail, where human rights are saved and preserved, instead of the despots profiting of a modern society. Like searching for a perfect escape from a sordid reality, Etcheverry tries to ‘fix’ the outcome from the negative impact that a world that excludes so many, caused in the mind and soul of its members. The human spirit prevails in wonderful trips as “a bird that crossed the sky of fire, casting over the world the texts of what is called the operative Magic.” Despite the criticism and cynicism from the diary of Alberto Magno, the lines of “his” literary Alberto Magno, the lines of his faithful belief in humanity pour out in some of the lines: “And like this as a species of spiritual animal, overfed and misbalanced, impregnated over all existence in the Middle Ages, amplified to the square by technology that ended demonstrating that the ideas, religions and beliefs flowing over the grey world that doesn’t produce only dragons burning the skies, but also other entities, Greta Garbo and I leave the reality flow according our desires …”. Read this book, it will make you think. You will enjoy the reading. Etcheverry writes in this book about themes that are important, such insertion, acclimatization, dislocation, language decay and the search for the common in us. We share with him his love for the continent. His search, is a continuous search for making people from “the other Americas” more recognizable to the North. Jorge Etcheverry, born in 1945, is a former member of the School of Santiago and Grupo América from the 1960s. He lives in Canada and has published poetry, prose, criticism and various articles in several countries. His books of poetry are: The Escape Artist (1981); La Calle (1986); The Witch (1986); Tánger (1991); A Vuelo de Pájaro (1998); Vitral con Pájaros (2004); and Reflexión Hacia el Sur (2004). Lately, he has appeared in anthologies such as Cien microcuentos chilenos (2002); Los poetas y el general (2002); Anaconda, Antología di Poeti Americani (2003); El lugar de la memoria. Poetas y narradores de Chile (2007); Latinocanadá (2007); Poéticas de Chile. Chilean Poets (2007); 100 cuentos breves de todo el mundo (2007); and The Changing Faces of Chilean Poetry: A Translation of Avant Garde, Women's, and Protest Poetry (2008). Heart Wood Reviewed by Mariela Griffor Author: Eric Torgersen Publisher: Word Press (http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/heart-wood-eric-torgersen/1111096452) Poets often ponder about death. We make death a friend when we try to understand her. We go back to her to pick on its mystery but we leave, we always leave until one day she will get us with such force we will not return. Torgersen’s book is a reflection on past and present times in a collection of free verse and structured forms that gives a clear idea of his life. Some of the poems are early work never published in book form until now. The strong, forceful, youthful view of the landscape that he inhabits offers us a window into a nostalgic look of a youth that escapes the body but never the mind. In the mind resides the tenderness, the sweetness, the enchantment of earlier years. He looks back and enjoys the regrets into that past that was immersed in youthful spirit full of astonishment in front before the nature, man and its surrounding. The poems, centered in current years, are severe; he examines the virtues of life and death with interior peace that invites the reader to get close to his revelations and without anxiety, but only reflection, as in the poem ‘I will die in Lake Superior’. I will die in Lake Superior on an August night, naked because it is dark and I ran out of the sauna, all rosy and wrinkly in the candle light of the cabin, though in the dark outside no one will see, not even I in my last moments- thin moon, stars all blazing and boiling like I’m Vincent van Gogh, but I will have left my glasses in the bathroom I’ll feel that first chill grip as I hit the water, and think, “My heart is pounding, as it should be”; then I’ll dive in and go under once, again, and a third time as the pounding grows, as if something really large mean to be let in. I will turn to go back, but the dim light of the cabin will get farther and farther away, as if I were carried off by some huge wave. Torgersen is a genuine writer, always searching for truths that impregnate the page. If you read this book, you will not be disappointed. You will be frequently reminded of this poem where he describes night, night in the cabins surrounded by the chant of the cicadas when it is not winter. Michigan landscape is everywhere in the book but it is always the humanity of its habitants that takes the center stage like in The Horses: The Horses on learning late, of the death of Nicolas Born The Horses, Nicolas. Once we all drove out through corn to ride the rented horses. You had it first, the horse whose legs years had locked in a stolid walk; you kicked and pulled. You made good jokes. We circled you on our spry horses, laughing. No rider, afraid of a gallop, I gave up my good horse then and you rode her back to the barn in style. Long past that circle of laughing friends I ride the slow horse home. He highlights the connection between humans and horses, while putting that experience into our own interaction with the page. The language is carved by the motion of riding and the emotion of a long lost childhood. Eric Torgersen has published six books and chapbooks of poetry, two of fiction, and a full-length study of Rainer Maria Rilke and Paula Modersohn-Becker. He also translates German poetry, especially that of Rainer Maria Rilke and Nicolas Born. He was born in Huntington, New York. He has a BA in German Literature from Cornell University; after two years in the Peace Corps in Ethiopia, he earned an MFA in poetry from the University of Iowa. He retired in the spring of 2008 after 38 years of teaching writing at Central Michigan University. He lives in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan with his wife, the quilt artist Ann Kowaleski. He’s available for workshops and readings. While I thought that book clubs were a thing of the past,I found this wonderful virtual book club by Kristina Lugn out of Sweden. Imagine how much fun it would be to participate in the sort of club that is run by authors you love!

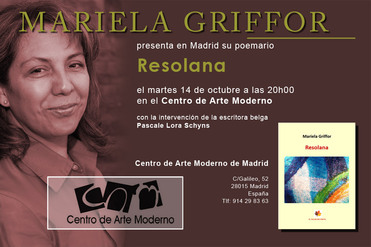

:-)! http://www.svt.se/kristina_lugns_bokcirkel/se-program/avsnitt-1-288?autostart=true  Interview A Northern Habitat: Robin Fulton Macpherson in conversation with Mariela Griffor By poetryinternational / October 27, 2014 / Interview / Leave a comment Interview with Robin Fulton Macpherson by Mariela Griffor Arran-born poet and translator Robin Fulton has spent much of his life in Norway, and has been active in the translation of Scandinavian poets into English. Robin Fulton Macpherson was born in Arran in 1937, attended primary school in Arran and Glasgow and secondary school in Golspie, Sutherland. He attained an MA in 1959 and PhD in 1972 from Edinburgh University. From 1969 to 1971 he held the Writers’ Fellowship, also at Edinburgh University. He was senior lecturer at Stavanger University in Norway from 1973 to 2006. His Selected Poems (1980) gathered work from five earlier volumes and was followed by two further collections (1982, 1990). Marick Press, Michigan, has brought out A Northern Habitat: Collected Poems 1960-2010.He edited Lines Review and the associated books from 1967-1976; Selected Poems by Iain Crichton Smith (1983); The Complete Poetical Works of Robert Garioch (1983) and revised Robert Garioch’s Collected Poems (2004), and A Garioch Miscellany (1986).His essays were published in Contemporary Scottish Poetry (1974) and The Way the Words are Taken (1989). Book-length selections in translation include Sekunden överlever stenen, translated into Swedish by Johannes Edfelt, Lasse Söderberg & Tomas Tranströmer (Ellerströms, Lund, 1996); Grenzflug, translated into German by Margitt Lehbert (Edition Rugerup, Hörby, 2008) and Poemas, translated into Spanish by Circe Maia (Rebeca Line Editoras, Montevideo, 2013. He has translated a goodly number of Scandinavian poets, such as Tomas Tranströmer from Sweden (most recent edition 2011), and Olav H Hauge from Norway (most recent edition 2011). See also Four Swedish Poets (White Pine Press, 1990) and Five Swedish Poets (Norvik Press, Norwich, 1997). His most recent translations are from the Swedish of Harry Martinson (Bloodaxe, 2010, Bernard Shaw Translation Prize) and Kjell Espmark (Marick Press, Michigan, 2011 and 2012). Mariela Griffor: You grew up in Scotland but have spent the last forty years in Stavanger, Norway. How did that come about? Were there family connections with Norway? Robin Fulton Macpherson: None at all. When people ask me why I came here and stayed I´m not sure if I can give convincing reasons. «I meant to stay here for two years and got stuck» elicits «So you like the place,» which in turns elicits «No, I hated it for many years.» So let´s get rid of this biographical bit at the start. Briefly – In 1973, after nine years of school teaching, two years holding the Writer´s Fellowship at Edinburgh University, a fresh Ph.D. in late medieval Scottish Literature and History, and two years of unemployment, I found that potential employers, especially of the academic sort, saw me as having too enigmatic a shape to fit whatever slots they had available. Unemployment has its inconveniences, and I felt obliged to take the first job I was eventually offered, at what was then a District College in Stavanger. I was to used English as the teaching language and was expected to teach subjects of which I was ignorant (e.g. English for students of economics, and an outline history of the U.S.A.). This was a bad career move – but I suspected I didn´t really have a career and as the years passed I realised that a job which left me energy and time to write is not something to moan about, not loudly at least. In due course the District College turned itself into a University (not perhaps a very convincing one) and it was clear that promotion within the system was something for non-enigmatic natives. My last couple of decades there saw me teaching rather elementary courses in translation and in nineteenth and twentieth century British History for first and second years students. It has never been part of my job to teach literature and I´m not sure if I´d have wanted to do so. I handed in my office keys in December 2006, five months short of my seventieth birthday. MG: Every year you take time off to go into some sort of vacation or trip. Do you do this often or is it only during the summer time? Do you get inspiration to write poetry in these trips? RFM: Apart from two or three sabbatical periods spent in York – we´ve spent so much time in York we feel it must be a kind of second home – summer holidays have seen us joining the milling crowds. We have driven around much of Northern Europe, within a range which «seasoned travellers» might regard as rather narrow. For various reasons we avoid flying. As for «inspiration,» simply getting out of one´s usual round can throw fresh light on some dark corner of the brain where an idea might be waiting for attention. Poems thought-up on the move must touch on the same concerns as poems written at home. MG: As a Scotsman immersed in the translation of Scandinavian literature, can you say which English and Scandinavian writers you admire? RFM: «Admiration» can imply a certain distance, or lack of deep personal response. In that sense I could say I admire Shakespeare´s use of English but I have no great interest in theatre (nor in opera or other large-scale pubic events). And «admiration» varies from time to time. When I was young(ish) I thought I admired Paradise Lost but when I became acquainted with La Divina Commedia my view of Milton clouded over a bit. Milton´s language is of course resounding and captivating but much less varied than Dante´s Tuscan, and Milton made the huge mistake of introducing the Trinity as characters, Christ appearing as a sycophantic son behaving obsequiously to the Managing Director (=God). Dante went to pains to keep God where He belongs, beyond our comprehension. Rather than «admiration,» I prefer the idea of returning to various works decade after decade, finding something new in them. In this respect I have to mention Dante again, though my ability to read his Tuscan unaided stumbles somewhat. Chaucer and the late medieval Scottish poets concerned me a lot in the late 1960s into the 1970s: I´m curious about my response if and when I return to them now. I´m sure there are still discoveries waiting for me in Robert Henryson. As a student I found that my eyesight wasn´t happy with voluminous reading of novels so I concentrated on the main English-language poets. This was not a good idea with regard to fulfilling syllabus demands but I think I developed a reasonable total view and can find my way about. I have no particular «favourites.» When it comes to «non-favourites» among the big names, I could mention Robert Burns, Ezra Pound and Hugh MacDiarmid, which means I am probably weighed and found wanting. Scottish poets active in the second half of the twentieth century form a special group because I knew many of them personally and I edited some of their work for magazines and books. I am now watching how my responses to the older generation are altering. Many thought it was our duty to admire everything MacDiarmid said and wrote: what I found off-putting were his self-promotion and the antics of those around him. Many found it hard not to admire Sorley Maclean, which was fair enough in its way, but a proper appreciation of his achievement relies on a proper knowledge of Gaelic. Norman McCaig was very popular with audiences and I now feel that he was at his best when not so intent on immediate listeners. Edwin Morgan was more widely popular, inventive and optimistic right into a very old age, but I have to confess to finding it difficult to locate, or sense, his real obsessions. There is no doubting the real obsessions in the work of Iain Crichton Smith and I can return to him whenever I want, even if wishing he had been less impulsive and hasty. Of the poets writing in varieties or variations of Scots it is Robert Garioch who keeps my admiration. He was a skillful verse craftsman who combined an intimate knowledge of Scottish history with a full awareness of the events of twentieth century Europe. Throwing a glance over the Atlantic, at the older American poets, I dip into Wallace Stevens now and then, without disappointment. At one period I read everything written by John Berryman and Robert Lowell but am not at all sure if I’ll repeat the experiment. Then you ask about Scandinavia. I´m afraid there are great holes in my knowledge here. In the 1970s (perhaps) I worked through both Ibsen and Strindberg, but haven´t yet revisited them. I have translated poems by Bo Carpelan (Finnish-Swedish) and Henrik Nordbrandt (Danish) but otherwise my knowledge of Finnish and Danish literature is a disgraceful blank. After much effort I managed to produce what I still feel are reasonable translations of Olav H Hauge, but he is the only Norwegian poet to whom I have been able to respond closely. If my knowledge of various literatures falls far short of professorial standards the reason is that for most of my adult life I have been more engrossed in music, literary interests then being marginal and fragmentary. It´s a matter of what has the greater impact on me. For example, the symphonies of Sibelius, from the third to the seventh, affect me more than almost anything from Scandinavia which I have merely «read.» I hope this doesn´t raise disappointed eyebrows on the Swedish poets whom I have spent much time translating – we can return to them later. MG: You are from Arran. How has the geography and language of Scotland influenced your writing? RFM: I´m not sure if they have. But of course some readers might see, or think they see, more than I can. Most people feel they have a strong connection to the landscapes in which they grew up and my own sense of belonging to Scottish Highland landscapes is of course intense. A «sense of belonging», however, is an elusive concept, especially since it seems to change as the years pass. The «other» country becomes very familiar but will always (at least in my case) remain «other,» while «one´s own» country keeps changing with the times in one´s absence. Some of my poems, not surprisingly, nibble or nag at the resultant feeling of unease. I was born on Arran, where my father was a Church of Scotland (i.e. Presbyterian) minister, and spent my first seven years there. The island is off the south-west coast but in spite of its Lowland latitude its history and landscape have been more Highland than Lowland. Before the war was over we moved to Clarkston, a suburb on the southern outskirts of Glasgow, and then after three and half years moved again, this time up to Helmsdale, a fishing village on the east coast of Sutherland. The reasons for these moves were never given to me and I still don´t know what they might have been. As for language, my father´s people were from the Borders and seemed to have a fair amount of Scots vocabulary but maybe didn’t use it much. My mother´s people were from Sutherland and Caithness and must have had Gaelic at least up to my grandfather´s time, but he didn’t use it. The English we used in the Highlands was easily distinguished from the English used by people in the Lowlands; among older people, there was ghost of Gaelic behind it. At school in Sutherland, Lowland Scots , which we came across mainly in the poems of Burns, felt almost like a foreign language and I never developed any kinship with it. MG: Can you tell us a bit about your family and how the writing interest was born? RFM: In the early 1930s, in Edinburgh, father took an Honours degree in French and mother took one in French and German. Father went on to train as a minister and mother taught for two years in Helmsdale. As far as I could see, their interest in French and German ended there, as if their studies had become detached from the rest of their lives. They never read anything in either French or German. Father laboured over the elegant periods of his sermons, which were duly admired. As was clear from her letters, mother could turn out a good sentence. But «literature» was something else. I had no special interest in writing until my student days were almost over. In my last year I showed samples to one of my tutors, hoping for advice, but he was snooty and remarked that I must have been reading too much T.S.Eliot. When in due course I started having poems published in papers and magazines, I strongly suspect that my parents regarded this as a reprehensible form of exhibitionism. I have no idea where or when or how a «writing interest» was born. In my boyhood, as was not unusual, my interests were perhaps like those of a budding scientist. In my youth, music took over. My four years as a student were split fifty-fifty between Edinburgh and Helmsdale and in Edinburgh I had no access to a piano. Maybe I began writing as a kind of substitute, but it must have been rather a meagre and silent one. MG: How is your writing process? RFM: When I come across a poem which catches my interest, i.e. which asks me to return to it later, I can´t say I feel any curiosity about the struggles the poet may have had. Some poems enter the world more or less intact, while others require much huffing and head-scratching, but it´s only the finished product that matters. Academic careers may well be enhanced now and then by hours spent in hushed libraries staring at the scribbles of deceased poets, but how often are the results actually useful to readers? My own hours of staring at the rough drafts left or donated by various poets roused in me the rather sullen and unsubtle conclusion that second thoughts are sometimes better than first thoughts, and sometimes not. I think there´s a good case for poets getting rid of all early drafts and messy first versions. Librarians wouldn´t like this, of course: they are so neutral, but I suppose they have to be. In the 1960s a flattering librarian in Edinburgh prised out of me a notebook with pencil jottings, an episode I regret. I have tried several times to persuade his successors that the notebook is a waste of space and ought to be recycled, but they are adamant, as if they were sitting on a national treasure. I can´t imagine that there could be anything about my way of writing poems that would be of interest to others. I have an impression that when a poem starts it does so almost surreptitiously, in some corner of the brain I´m not looking at just then. Perhaps I have to be quick and careful to catch it without squashing it before it can scuttle back into a crack. I spend very little time with pencil and paper, preferring to piece together poems in my head. I don´t talk about poems-in-progress, not even to myself, for that would scare the perhaps-poem away. I don´t feel much inclined to talk about my poems when they´re finished, for by then they´re off on their own. (Some may, on reflection, turn out to be duds, but that´s another matter.) If I think about it, I see my poems as reaching readers rather than listening audiences. Once «finished» or «ready», my poems have a way of disappearing from me. I simply forget them. I can´t quote a single one from memory. I´ve even seen poems of my own in print without recognizing them. Perhaps this means I´m not really a poet, or a poet only incidentally and occasionally. But we could wonder how we define a poet – is a poet a poet only when he or she is actually putting together a poem, while behaving normally, i.e. not being a poet, the rest of the time? If I let a few weeks go by without setting together words into some shape I find satisfactory, I start to feel restless. I don´t twitch, or start behaving in a bizarre manner in public, but I do feel I might be neglecting something. MG: How is your translation process? RFM: I have never worked as a professional translator, not being qualified to do so, and not wanting to do so either. The only language I learned within educational walls was Latin, up to «First Ordinary» at Edinburgh. I even taught Latin at a posh school, starting the day with it five days a week for several years. (Crossing Edinburgh by Corporatoin bus was a bad start to any day, but a dull hour of elementary Latin was therapeutic.) I´m familiar with Norwegian after forty years in the country, though my use of it is not as fault-free as it ought to be. My knowledge of other languages is of the reading kind, i.e. patchy, but I am much taken by vocabulary and etymology and gammar in different languages. My reading knowledge of Swedish is reasonable, after much reading, but I have to be wary of gaps. My interest in different languages is closely related to, or a part of, my interest in how words work in poetry. I read quite a lot of non-English poets, but only in parallel text editions, where I can see, as far as I can, what is going on. Recent examples include Homer Aridjis, Sarah Kirsch and Jean Fallon. I started to learn Swedish just because I liked the sound of it. Then I met some poets and I tried to translate their poems. I was very rash and my first published efforts were ruined by howlers. But if I hadn´t jumped in, perhaps I would have got nowhere. I had no Grand Plan to introduce Swedish poets to the English-speaking world. I simply picked out poems which I fancied and which looked as if they might work tolerably in English. And so a long-term and gradual process had begun, almost by accident. I never translated much at a time, but in the course of several decades some of piles of paper became big enough for books. Eventually, various editions of «complete» Tomas Tranströmer were published, and substantial selections of Werner Aspenström, Kjell Espmark, Harry Martinson, Lennart Sjogren, and Östen Sjöstrand. Shorter selections appeared of Lars Gustafsson, Gunnar Harding, Eva Ström, Staffan Söderblom, and others. The Martinson volume was the only one done »to order,» at one go. The rest grew piece by piece. Ventures into prose included a volume of short stories, Stig Dagerman´s German Autumn and Pär Lagerkvist´s Guest of Reality. Putting a complicated matter very briefly, my approach to the translation of poetry has been that, while there is a place in the universe for adaptations and imitations, the word «translation» ought to be kept for attempts to be as faithful as possible to both the letter and the spirit of the original. That´s utopian, which is why I feel so ambivalent about poetry translation and why every now and then I wish I had never started, and I try to stop, but then, since there´s an element of obsession or addiction about the activity, something catches my attention and I begin to poke at it and I´m off again. The poets I have translated have been helpful with explanations and information. One or two failed to point out howlers when they must have known they were there. The most satisfactory cooperaton I´ve experiencd has been with Kjell Espmark: we´ve been translating his poems, on and off, for about forty years, aiming at a faithful representation of his Swedish combined with an English readability. Here and there we have observed the roles of poet and of translator overlapping or even temporarily merging in subtle ways. MG: Did you ever want to write fiction? RFM: In my twenties I wanted to write short stories but my experience of life was too limited. I read the short stories of many masters, especially of Chekhov. At one period I had learned enough Russian to make my way through Chekhov´s own words, and after that any English version I looked at seemed tasteless, like whisky vandalized by an excess of water. MG: You have a tremendously exquisite sense of humor that I enjoyed after each correspondence. What role does humour play in your writing? RFM: My poems aren´t hilarious and aren´t meant to be, of course. Jokey verse has often lost its charm before the ink has dried. But as for being serious, there are different sorts. The boring sort, incurious and grinding slowly from A to B like a wheel on a rail, leads us nowhere. But the other sort, constructive and liberating and imaginative, has within it an essential element of playfulness, whether the play is with words or shapes or sounds or ideas. We lose something important if we lose the infant´s curiosity, the capacity to try things out, even if it just means turning an object upsides down to see what happens. I´d like to think that the right sort of radar can detect a playfulness somewhere beneath my poems. MG: In «Anxieties of an Insider» in your 1971 collection you use the second person pronoun: was that a reference to an individual, your culture or your language? RFM: This poem was written in the spring of 1970 and was occasioned by a long, chilly, damp day visiting a small Buddhist monastery somewhere in the south-west of Scotland. I see the poem now from the outside, at a great distance, as if someone else has written it, and can only guess about what was / is going on. It seems that the speaker in the poem is perhaps the temple itself, or more likely someone who feels secure, or wants to feels secure, in an inside that appears to replicate the outside but in an idealized form. The «you» is me, the outsider who intrudes, bringing in unwelcome and threatening questions. The «bandage» in the last line is ambiguous, suggesting both damage and healing, but whose damage and/or healing is an open question. The poem was a response to a particular occasion and I doubt if I intended any wider reference to culture or language, and it was not intended as any sort of comment on Buddhism as such. There is a discomfort in my earlier poems which causes me discomfort now, so I don´t look at them unless I have to. A generalized anxiety, sometimes taking the form of a sense of entrapment, seems to lurk behind many of my earlier poems, and I can understand why some reviewers of my efforts complained that I was too «clinical.» Whatever was bothering me, in a subterranean way, appears to have eased off in the course of the 1970s: «The Change,» written early in 1973, suggests the start of such a process. MG: In «The Spaces between the Stones» there is a metaphorical reference to men in yellow helmets. Can you explain what that means? RFM: I suspect this was literal rather than metaphorical. I wrote this poem sequence in 1969, mostly in Edinburgh University Library in George Square, or at least in what was left of George Square after the university had knocked down half of it. On the way there one day I watched men demolishing another old bit of Edinburgh, and their helmets just happened to be yellow. MG: Are you a religious man? Can you develop a bit on the reference to Uppsala Cathedral («The Cold Musician» Part 2)? I lived in that city for almost 14 years so I´m very curious as to how that poem came to be part of the book. RFM: In the spring of 1970, just about to reach the ripe age of 33, I went abroad for the first time, and heard foreign languages around me for the first time. I made the journey by train from Edinburgh to Stockholm and back. I gave talks at the Universities of Uppsala and Göteborg, where I took care to talk slowly, thinking I was speaking to Swedes, only to find out afterwards that most of my listeners were American post-graduates. Their interest in how religious views affected the way in which late medieval people saw the universe was less than mine. A while later, someone sent me a postcard showing Uppsala cathedral on a clear winter afternoon, so that went into the poem, along with the figure of Luonnotar, from the Kalevala, subject of the well-known tone-poem Sibelius wrote in 1913. «The Cold Musician» is a rather miserable little sequence about coldness, but at least the cold doesn’t have the last word. I like wandering around cathedrals, York Minster being the one I´m most familiar with, and I see them as more living than the ecclesiastical relics of Philip Larkin´s «Church Going.» How the masons of the Gothic structures made tons of stone appear to weigh almost nothing has often been explained but we still can´t quite believe what we see. When the great cathedrals of Northern Europe were being built, there were of course mistakes and disasters – but modern buildings also fall down now and then. Apart from their beauty, such buildings also give us mixed messages: their purpose was the glorification of God, we assume, but they were also products of human pride. Humble piety alone never rose such towering edifices: they needed gross ambition, stubborn effort sustained over not just decades but centuries, and money on a truly grand scale. We may think of Dean Jocelyn, in William Golding´s 1964 novel The Spire, driven by his obsession beyond any rational accountability. The remarkable, real-life Abbot Suger, responsible for the reconstruction of Saint-Denis, on the north side of Paris, knew what he wanted, tirelessly, and achieved it. He aimed to glorify both God and France and its Kings; the opening celebration in June 1144 was a very grand PR occasion, not least for the Abbot. Am I a religious person? That depends on what you mean by «religious.» You´d have to spend a lot of words explaining that, and then I´d have to spend even more words answering you, and we might finish up with a labyrinthine and probably banal book of little use to people setting out to read my poems. The briefest answer I can give would be that since my teens I´ve been engrossed, sometimes perplexed but always fascinated, by the basic tenets of Christianity as they have come down to us through the generations. They have reached us by a bewildering variety of routes, some through dubious-looking shadows, some through innocent-looking sunlight. They have been misappropriated by an endless series of cranks, swindlers and despots. We have to look at them with clear and sceptical eyes, but at least they have reached us and will survive us. Just as the Church was seemingly founded on a rock that was split, so the matter of Christianity is contained in a small number of texts which appeared to survive by chance. The four Gospels (plus the extra fragments that were lost then found) were written, like most «historical» and religious works through the ages, with polemical aims in mind, and they have been relentlessly glared at and interpreted and misinterpreted for close on two thousand years. I find them enigmatic, disturbing, and often marked by teasing lacunae and things not said. Whether these rather general remarks can be seen to have much direct bearing on my poems, I can´t say. Some of my early poems, mostly by now confined to oblivion, had specific Christian references, but I soon realised that these had no poetical function and I dropped them. If there was any kind of turning-point it can possibly be seen in «In Memoriam Antonius Bock,» a set of thirteen poems which I wrote in the winter of 1972-73. (Block is the Knight in Ingmar Bergman’s Seventh Seal.) I wasn´t sure at the time, and am not sure now, how I managed to write it, but I feel certain that I would not want to consign it to oblivion. One of the ideas behind the set is that if we want certainty about first and last things, we can´t expect to find it, so we have to accept that uncertainty and doubt are essential aspects of faith. This is leading us into abstractions, which I don´t care for because they drag us away from the specific nature of the poems. MG: Thank you for your time Robin Fulton Macpherson. It is always a pleasure to be able to share time with you! Please click here to read poems from Robin Fulton Macpherson’s A Northern Habitat  I'm thrilled about my fall readings –introducing the first poetry collection in Spanish Resolana--( Madrid, Pontevedra, Valencia, Andalucia, Cantabria) and grateful to El Taller del Poeta, for putting together this book in Spain: MADRID

Centro de Arte Moderno C/Galileo, 52 28015 Madrid, Spain Tuesday October 14, 20:00 hrs. http://www.centrodeartemoderno.net/?view=magazine PONTEVEDRA FUNDACIÓN CUÑA - CASASBELLAS de Pontevedra Sala Versus Calle Gerardo Alvarez Limeses 36001 Pontevedra, Spain Wednesday, October 15, 20:00 hrs. Hosted by family and friends of Manuel Cuña Novás http://www.hipofanias.net/fundacion/Inicio.html VALENCIA Ubik Cafe libreria Cafeteria Calle Literato Azorin,13 Ruzafa 46006,Valencia, Spain Thursday, October 16, 20:00 hrs. http://www.ubikcafe.blogspot.com/ ANDALUCIA Biblioteca de Huercal de Almeria Plaza de la Constitucion, 2 04230 Huercal de Almeria, Andalucia, Spain Friday October 17, 18:00 hrs. La Oficina Almeria Producciones Culturales Calle Las Tiendas, 26 04003 Almeria, Andalucia, Spain Friday, October 17, 22:00 hrs TORRELAVEGA Sez Turuta Calle Santander,1 39300 Torrelavega (Cantabria), Spain Saturday October 18, 14:00 hrs. MADRID La Marabunta (Libros y Café) C/Torrecilla del Leal, 32 28012 Madrid Wednesday October 22, 20:00 hrs. <Lavapiés> Friday, August 01,

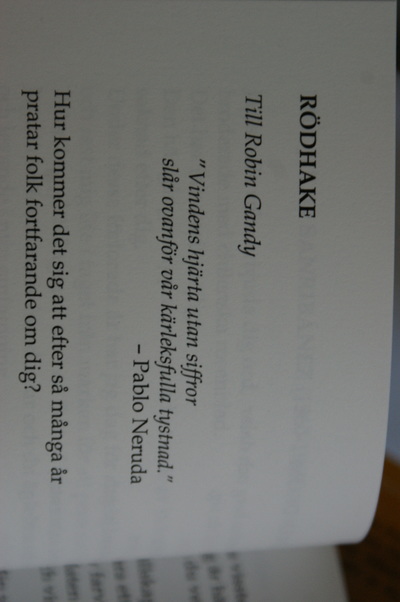

2014 Mariela Griffor: The Psychiatrist Child’s Eyes People say that children see and hear things they themselves cannot see or hear, and this child breaking into the room to hug and kiss his grandmother, Wilma, hasn’t seen me yet. I am afraid of his eyes, touching like a hummingbird the cornea of my eyes. I don’t want him to see the puddle of old pain and rusty love that grows inside of me, the spider web of my disappointment, a beaten heart that has never overcome the loss of him. I am afraid of this child running around with his two frank years, afraid of me breaking. I’m sure he would scream if I let my pupils touch his, and the room would look at me knowing the truth of what he sees. I am afraid and old, smashing day after day a memory of innocence. I know too much. My mind is futile. This is a favourite poem of mine from “The Psychiatrist”, Mariela Griffor’s latest collection, sent to me for review by Eyewear Publishing last year.Searingly poignant, simply put, the poem expresses — in a way I don’t think I’ve seen elsewhere — how one can feel confronted and even intimidated by the innocent life force of a young child.With this poem, I have only one — albeit small — quibble: it’s with the antecedent of the pronoun “him” in the line “has never overcome the loss of him”.We can assume it’s not the child itself, but a man, an adult love to which she is referring — Ignacio, perhaps, mentioned in an earlier poem, or the unnamed subversive in “Love for a Subversive”, the unnamed lover in “Rain”? There is probably some way around this, but at the same time, that pronoun in this poem has its own brute force. Mariela Griffor was born and raised in Chile, and came into adolescence and early adulthood under the Pinochet regime.As a young woman, she joined a revolutionary group, and doubtlessly ended up on a blacklist.In 1985, she left Chile for Sweden under involuntary exile.Much later, in 1998, she moved with her American husband and two daughters to the United States, where she is now Honorary Consul for Chile in Michigan. Here are poems of subversion, exile, and solidarity that ache to be told: elegies for friends who were tortured or disappeared, evocations of nights of insomnia, furtive meetings under code names, a character sketch of a relative who was a possible undercover agent for DINA (National Department of Intelligence.) All contemporary Chilean poets – indeed, Latin American poets – write under the shadow of Pablo Neruda.Indeed, Ms. Griffor will soon be coming out with a new translation of his Canto General, published by Tupelo Press. Her own style, though, doesn’t bear a trace of his lush, surrealistic influence.She reminds me of certain Eastern European poets — Czeslaw Milosz, Tadeusz Rozewicz, Wislawa Szymborska among others — or of her own countryman, Nicanor Para: poets that speak unvarnished truths with simple irony and measured declaration. In some later poems in the collection, the Griffor’s free verse becomes rather too prosaic for my taste: My grandfather did not talk about what Mr. Monzalves said, but it was clear that he knew that my grandfather was a sympathizer of Allende and that he had come to deliver a warning. Just before I left Chile the last person I met from the Front in Santiago was my commander His real code name was Wolf. I told him I was planning to leave the country because I could not avoid the surveilland anymore and my good friend, the lawyer Inunza, had arranged for me to go to Sweden or France. (Exiles) In a patch like this one, I wish that the author had fashioned an introduction or searched more deeply for lyricism in her subject matter. In most places, though, her straightforward style has its own strength and sensibility. The title of the collection raises expectations that it will concern mental illness, or perhaps relate a series of psychiatric consultations. The brief title poem, however, is the only one where a psychiatrist is featured; there he figures as a voice of authority in the narrator’s head that the poet summarily shoots down to get on with her life. Mariela Griffor’s “The Psychiatrist” is well worth buying and reading.I look forward to seeing more of her work.  The latest in my irregular series of Poet’s Soapbox reviews is a solicited article, in that the editor of Eyewear Publishing approached me directly to provide a review of Mariela Griffor’s first UK collection of poetry. I agreed, without quite realizing how long it would be before The Psychiatrist made it to the top of the ‘To Do’ pile. I haven’t seen the final print form of the book; this review is based on a proof manuscript so is guided solely by the substance of the poems, not the look and feel of the book itself. I have to confess at the outset that my knowledge of Latin American poetry extends not much further than a few Neruda quotes. I’m aware of the dangerous political environment in which many of the great names were writing, and of the long shadow that the 20th-century dictatorships cast over every writer within this tradition; but I’m still largely unfamiliar with the works themselves. As a newcomer, therefore, I’m grateful that The Psychiatrist is a collection which presupposes no prior knowledge of South American literature and only modest familiarity with the politics of the region. This is a highly accessible collection; its clarity is never impeded by unfamiliar references. It even provides a miniature glossary at the end, where a small number of phrases are briefly explained. The collection spans poems written between 1986 and 2011, charting the poet’s path from Chilean revolutionary to exile in Sweden and, later, the US. The work is heavily autobiographical, or at least biographical – it isn’t clear how much poetic licence has been taken with the more startling stories, but what is clear is that this writer has lived through turbulent times. It’s hard for cosy British poets, with their cloistered poetry readings and expensive writing courses, to honestly understand the ‘other’-ness of a world where being a writer can make you a political threat, a military target. It is to Griffor’s credit that she gives us a glimpse into that world without sensationalising her past, and without any exaggerated claims as to her own role in the struggle. Despite the autobiographical tone, this collection doesn’t follow a linear narrative arc. Glimpses of the poet’s past are given in snapshot form, without chronology, allowing the reader gradually to piece together a rustic childhood, a great love, a violent bereavement, then exile and motherhood and a coming to terms with the past. The dead lover looms like a ghost over these poems; but what is most intriguing is that we never really get to see more than a shadow of the man. We infer an outwardly conventional marriage (at least, in the sense that elderly relatives are happy to embroider blankets for the couple), an academic career, a circle of intellectual friends – and then the revolutionary stuff, the death. But these are no more than glimpses. Only the penultimate poem, Chiloe Island, offers any kind of linear narrative, eventually stringing these threads together in a coherent whole: “...When he came back to the hotel, after his lens in photography class saw everything, we ran up the street... ...He made me promise if we ever had a child, and if he was not there, I would leave the country.” The poems themselves are un-fussy free verse, with plenty of white space to let the words sink in. The language is unpretentious and there is a striking lack of imagery. Those physical images which do carry emotional resonance (flowers, rainbows, blood, long corridors, guns and ammunition, the aforementioned blanket) do so by way of unsurprising metaphors, and I did wonder at first if this was a weakness of the collection. But actually Griffor is a very fine descriptive poet. Like the dead husband, she has a photographer’s eye for the telling snapshot image: “In Detroit it is easy to see pheasants walking the alleys, or children running like a flock hunting a dog, murals of Jesus, Martin Luther King, Bob Marley or BB King on dirty walls, pink, velvet sofas covered by bags full of garbage...” (from Selective Exposure) “The night before your call, I dreamt of the ocean: cold, dangerous, deep, dark, blue at dusk and dawn...” (from Thirty: just in time) “...They had gardens where the sun rose face to face with the sand. They had rainbows, like us, thirsty and wild. They had emptiness like us...” (from In Manistee) The poet is content to let the visual pictures tell their own story, without imbuing them with more than their fair share of significance. The emotional heart of this collection lies in the poet’s personal struggles: with exile, bereavement, motherhood. “What do we do with the love if you die?” demands the first line of the second poem, Love for a subversive – a question that rings like gunshots through all the poems that follow. Accusations are levelled against the poet’s mother – “Here I see her, her face in a duel with the sun... I see my pink communion dress in her hands. I do not know her smell” (from Parade) – and grandmother: “She hid her smile to use against us. So powerful, so invisible... Even war is not so cruel” (from Cyanide Smile) – though when the narrator herself becomes a mother, a reconciliation of sorts is reached: “...The last paragraph of the letter said ‘I hope now when you are a mother yourself you can understand your own mother a little bit better.’ I couldn’t answer her. Not because I didn’t have anything to say but it was so hard to say it.” (from A Mother Thing) It is in these poems that I begin to suspect a hint of unreliability in Griffor’s narrator. In other poems in the collection, her childhood memories verge on the rose-tinted, and it’s not until she arrives as an adult in Santiago that the conflicts really begin: “I assassinate the old days with nostalgia. I don’t see but invent a city and its people, its fury, its sky...” (from Prologue I) The title poem of the collection brings these conflicts and contradictions graphically to the fore. Manuel Fernandez, the psychiatrist who guides the poet through her traumas, becomes a hate figure for the narrator precisely because of his reasonableness: “You are suffering a post partum depression, he told me, before I shot him, like the many other voices in my head.” At its best, The Psychiatrist is a vivid, engaging collection. It’s full of colour and fine description, peopled with outlandish characters – from the pipe-smoking mathematician Robin Gandy, who laughs “the way / a beggar laughs in children’s tales: / smoky and loud”, to the stern taskmaster Andres the Barbarian, “the man who hit me in the head / every time I forgot the letter ‘H’”, by way of a colourful string of revolutionaries with code-names like Wolf and Daphne. Griffor’s sadness for the country she abandoned and for the friends left scattered across the world is palpable: “...You and I will order two Napoleons and two coffees. We will sit at the table, you will look around to check if everything is the same... This time you give me your list, full of incomprehensible requests: go to Mass on Sundays, talk to the girls. I will bring my chair closer.” (from The middle of this goodbye) Where I had difficulties with the poems, these largely seemed to arise not from the storytelling but from the translation. My proof copy contained no translator’s details, so I’m unclear how many of the poems were originally written in English, or whether Griffor made her own translations of any that were not. In the earlier poems there are a number of weaknesses in the choice of words and in the phrasing and layout of stanzas, which I suspect would not have been there had the poems been presented in the poet’s first language. Line breaks happen haphazardly, often on unimportant words (“a”, “the” or “of”). Poems full of dramatic portent fizzle out and end with seemingly inconsequential domestic detail (Death in Argentina). Abstracts abound: “innocence”, “truth”, “disappointment” (Child’s Eyes); “certainty”, “regret”, “indifference” (Heartland). A few poems (Heartland; Boys) seem to be nothing more than lists of rhetorical questions. These blemishes gradually disappear on progressing through the collection – presumably a reflection of Griffor’s increasing ease with the English language in the later poems. The political narrative, too, evolves, becoming a backdrop for the personal. Stories of tyranny really matter, and it’s important that they are shared; but for me, those stories became so much more moving when the poems progressed beyond reportage, and Griffor allowed me to glimpse how they shaped her narrator, with all her contradictions, years after the tragedy and the exile. The strengths of this collection lie in the accessibility of its language, the breathtaking clarity of the descriptive writing, and the gradual empathy that Griffor elicits for a complex, not overly reliable, but always compelling narrator. The Psychiatrist is a thought-provoking introduction to an important genre within western poetry, and a salutary reminder to English poets that we should never take our freedom of expression for granted.

A REVIEW OF MARIELA GRIFFOR'S, THE PSYCHIATRIST (Eyewear Publishing, London, UK, 2013) by Carol Frost Near the end of Mariela Griffor’s powerful collection of poems, The Psychiatrist (Eyewear Publishing Ltd, 2013), readers learn of a woman’s promise from the narrator’s point of view to her lover to leave Chile “if we ever had/ a child, and if he was not there” (“Chiloe Island”). The personal promise explains a lot about the sense of heartbreak that lingers throughout the poems and about Griffor’s restraint in presenting a history of Pinochet tyranny. The relatively late revelation isn’t a ruse to keep readers in mystery but evidence of the author’s artistic decision to keep the difficult and complex events leading up to and after her exile just as they were. Lesser writers may have been unable to restrain themselves from giving readers a handle early—this is my story. I was victim, hero. The heartbreak in Griffor’s poetry is deeper than one person’s; she speaks for a country’s grief. It is only right that the reasons for her own grief are delayed. The style of the poems is the style of memory. Griffor’s stanzas and lines with their necessary abstractions, as in “My mind is futile” and “I learned/ their laughter before code names,” and intense sensory notation are not placed for rhetorical convenience but as they might occur while musing aloud. As Griffor invents the “new sounds, new men, new women” to tell the story of the war waged by Pinochet and his followers on Chile’s “own sons and daughters, her poems bend and extend to accommodate the different dimensions and perspectives of idealism, insurgency, betrayal, brutal policy, grief, and secrecy that the book explores. The poems present the coup and changing allegiances, the torturers—“Romero, Quezada, Coleman”—the “group” of leftists she was a part of, the codes and secrecy, and American complicity. There are poems, too, about family ties, of innocence and difficulty, of love in the time of strife, and death—by bullets and for one friend, Mauricio, by an addiction to Lucky Strikes, described in “Death in Argentina” as an irony. The topics are affecting in their own right, but Griffor’s strength is in the surprising intensity of her details. “Sometimes I drink water from the faucet,” she recalls telling Mauricio to temper the fantasy about her she knows he has developed. The detail and the motive for her telling him seem absolutely real, but there is something else about the line—the ungainliness and modest impropriety that we also recognize as real that intensifies the image. Another example of Griffor’s skill with detail comes at the end of “Exiles,” when speaking of having left Chile for Sweden, having left spring for winter, she tells that it was “the coldest winter in one hundred years/ with a mean temperature of -27.2 C in Vittangi.” The uncanny cold weather, we realize, gives us some sense of the physical coldness she must have endured in her first year of exile but also the coldness she needed in order to leave family, friends, her dead beloved, and her country. The Psychiatrist gives lessons about how to write political poetry. Individual lines in individual poems may seem a bit soft, lines like “Did their bodies and souls/ escape deterioration?” and “I don’t know with any certainty/ what to do next,” but overall the poems are challenging, substantive, and full of the art that is too often made subservient to craft. CAROL FROST's twelfth book of poems, Trilogy, is forthcoming in the fall (Tupelo Press, 2014). Others of her books include Pure, Love and Scorn, and Honeycomb. Four Pushcart Prize anthologies have reprinted her poems, and she has been the recipient of two NEA fellowships. She is the Theodore Bruce and Barbara Lawrence Alfond Professor of English at Rollins College, where she directs the yearly literary festival, Winter With the Writers. |

Name: Mariela Griffor Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed